The main task of skeletal muscle is contraction and relaxation for body movement and posture maintenance. During contraction and relaxation, Ca 2+ in the cytosol has a critical role in activating and deactivating a series of contractile proteins. In skeletal muscle, the cytosolic Ca 2+ level is mainly determined by Ca 2+ movements between the cytosol and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The importance of Ca 2+ entry from extracellular spaces to the cytosol has gained significant attention over the past decade. Store-operated Ca 2+ entry with a low amplitude and relatively slow kinetics is a main extracellular Ca 2+ entryway into skeletal muscle. Herein, recent studies on extracellular Ca 2+ entry into skeletal muscle are reviewed along with descriptions of the proteins that are related to extracellular Ca 2+ entry and their influences on skeletal muscle function and disease.

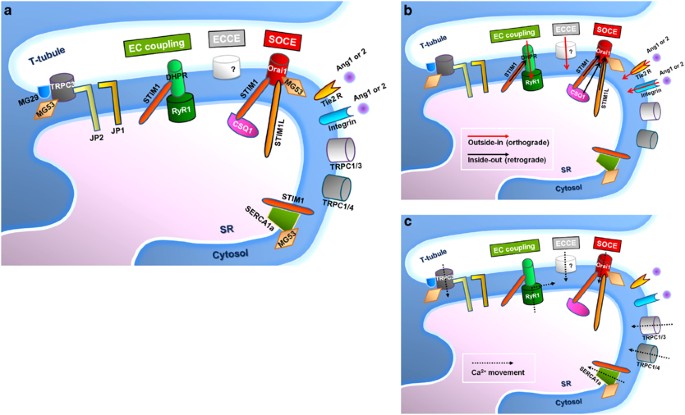

Skeletal muscle contraction is achieved via excitation–contraction (EC) coupling. 1, 2, 3, 4 During the EC coupling of skeletal muscle, acetylcholine receptors in the sarcolemmal (plasma) membrane of skeletal muscle fibers (also called ‘skeletal muscle cells’ or ‘skeletal myotubes’ in in vitro culture) are activated by acetylcholines released from a motor neuron. Acetylcholine receptors are ligand-gated Na + channels, through which Na + ions rush into the cytosol of skeletal muscle fibers. The Na + influx induces the depolarization of the sarcolemmal membrane in skeletal muscle fibers (that is, excitation). The membrane depolarization spreading along the surface of the sarcolemmal membrane reaches the interior of skeletal muscle fibers via the invagination of the sarcolemmal membranes (that is, transverse (t)-tubules). Dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs, a voltage-gated Ca 2+ channel on the t-tubule membrane) are activated by the depolarization of the t-tubule membrane, which in turn activates ryanodine receptor 1 (RyR1, a ligand-gated Ca 2+ channel on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane) via physical interaction (Figure 1a). Ca 2+ ions that are stored in the SR are released to the cytosol via the activated RyR1, where they bind to troponin C, which then activates a series of contractile proteins and induces skeletal muscle contraction. Compared with other signals in skeletal muscle, EC coupling is regarded as an orthograde (outside-in) signal (from t-tubule membrane to internal RyR1; Figure 1b). Calsequestrin (CSQ) is a luminal protein of the SR, and has a Ca 2+ -buffering ability that prevents the SR from swelling due to high concentrations of Ca 2+ in the SR and osmotic pressure. 5 It is worth noting that during skeletal EC coupling, the contraction of skeletal muscle occurs even in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+ because DHPR serves as a ligand for RyR1 activation via physical interactions. 1, 2, 3, 4 The Ca 2+ entry via DHPR is not a necessary factor for the initiation of skeletal muscle contraction, although Ca 2+ entry via DHPR does exist during skeletal EC coupling.

During the relaxation of skeletal muscle, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca 2+ -ATPase 1a (SERCA1a) on the SR membrane uptakes cytosolic Ca 2+ into the SR to reduce the cytosolic Ca 2+ level to that of the resting state and to refill the SR with Ca 2+ . 2, 6 An efficient arrangement of the proteins mentioned above is maintained by the specialized junctional membrane complex (that is, triad junction) where the t-tubule and SR membranes are closely juxtaposed. 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10 The triad junction supports the rapid and frequent delivery and storage of Ca 2+ into skeletal muscle. Junctophilin 1 (JP1), junctophilin 2 (JP2) and mitsugumin 29 (MG29) contribute to the formation and maintenance of the triad junction in skeletal muscle.

In addition to the feature of skeletal muscle contraction mentioned above, the importance of Ca 2+ entry from extracellular spaces to the cytosol in skeletal muscle has gained significant attention over the past decade. In this review article, recent studies on extracellular Ca 2+ entry into skeletal muscle are reviewed along with descriptions of the proteins that are related to, or that regulate, extracellular Ca 2+ entry and their influences on skeletal muscle function and disease.

Store-operated Ca 2+ entry (SOCE) is one of the modes of extracellular Ca 2+ entry into most cells. 11, 12 The existence of SOCE was discovered in salivary gland cells in the 1980s (referred to then as capacitive Ca 2+ entry). 13 After that, SOCE was rediscovered in mast cells and referred to as Ca 2+ release-activated Ca 2+ (CRAC). 14 However, the identity of the main proteins responsible for SOCE has only recently been revealed: Orai1 as a Ca 2+ entry channel in plasma membranes (also known as CRACM1); 15, 16, 17, 18 and stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) as a Ca 2+ sensor in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. 19, 20, 21 SOCE was originally thought to mediate only the replenishment of the ER/SR with Ca 2+ . It is now believed, however, that SOCE also participates in various cellular events that control various short- to long-term cellular processes such as specific cellular functions, the proliferation or differentiation of cells, and the onset and progression of diseases.

During SOCE, there is a rearrangement of some portions of the ER toward the plasma membrane (10–25 nm gap between the ER and the plasma membrane after rearrangement). 22 STIM1 dimerizes upon the Ca 2+ depletion of the ER, and relocates in the rearranged ER membrane. 23, 24 Monomeric Orai1s simultaneously oligomerize to form functional Ca 2+ channels in response to the rearrangement of the ER membrane and the relocation of STIM1, and relocate to the plasma membrane near the ER membrane containing STIM1 dimers. Finally, Orai1 and STIM1 form heteromeric oligomers called ‘puncta’. 25 In the formation of puncta, a highly conserved domain of STIM1 (known as the CRAC activation domain or the STIM1–Orai activating region) binds directly to the N and C termini of Orai1, and the binding of STIM1 to Orai1 activates Orai1 and allows extracellular Ca 2+ entry through Orai1. 26, 27 This entire process takes seconds to minutes, depending on cell types. 28

Homologous types of STIM1 or Orai1 have been identified and their functions have been under investigation: long form of STIM1 (STIM1L); STIM2; Orai2; and Orai3. 17, 29, 30, 31, 32 STIM1L is abundantly expressed in skeletal muscle, but much less in non-excitable cells. 30, 33 STIM1L generates faster and repetitive SOCE by the pre-formation of permanent clusters with Orai1 in skeletal muscle. 30 STIM2 has a role in SOCE in the mild Ca 2+ depletion of the ER, and regulates basal Ca 2+ levels in a store-independent manner in heterologous expression systems. 34, 35 However, the physiological roles of Orai2 and Orai3 are not as well defined as that of Orai1. 29

The crystal structure of Orai from Drosophila melanogaster reveals that a functional Orai channel is composed of a hexameric assembly of Orai subunits arranged around a central ion-permeating pore, 36, 37 which is markedly different from other ion channels (tetrameric channels are common in others). To activate Orai1, three dimers of STIM1 are required to activate a functional hexameric Orai1 channel. 24 The molecular structures of STIM1 and Orai1 have been intensively reviewed in recent articles. 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Orai1 has a cytosolic N terminus (that contains the N-terminal binding site to STIM1, a binding site to CaM and a Ca 2+ -dependent inactivation site), four transmembrane domains, a pore region formed by the first transmembrane domain (selectivity filter at E106, hydrophobic gate at V102, gating hinge at G98 and L95, and basic gate at R91) and a cytosolic C terminus (that comprises the C-terminal binding site for STIM1 and a coiled-coil domain). 44, 45 STIM1 has a short intraluminal N terminus (that contains a signal peptide, an actual EF hand and a sterile α-motif domain), a single transmembrane domain and a cytosolic C terminus (that contains coiled-coil domains, a CRAC activation domain/STIM1–Orai activating region domain and a lysine-rich domain). 19, 31, 43 The signal peptide (22 amino acids) that is predicted by the alignment of nucleotide sequences has been believed to target STIM1 to the ER (that is, ER retention at rest). 46 More studies on the ER retention of STIM1 have been conducted using heterologous expression systems such as HEK293 cells. 47, 48 Efficient ER retention of STIM1 depends on its lysine-rich domain and a di-arginine consensus site located in the C terminus. 47 The coiled-coil domains of STIM1 also contribute to the ER retention of STIM1. 48 The D76, D84 and E87 residues in the EF hand are critical for sensing the amount of Ca 2+ in the ER. 21, 49, 50, 51 The EF–sterile α-motif domain is responsible for the self-oligomerization and the relocalization of STIM1. 52, 53 The first coiled-coil domain participates in the oligomerization of STIM1 only at rest. 54 The lysine-rich domain is responsible for the Orai1-independent plasma membrane targeting of STIM1. 26

In skeletal muscle, extracellular Ca 2+ entry partially contributes to the Ca 2+ supply that is required for the maintenance of skeletal muscle contraction (but not for the initiation of skeletal muscle contraction, as mentioned in the Introduction). 11, 12 The existence of SOCE in skeletal muscle was identified in skeletal muscle fiber from adult mice in 2001. 11 In terms of a working mechanism, SOCE fundamentally differs from orthograde EC coupling in that the depolarization of the t-tubule membrane triggers the activation of internal RyR1 (Figure 1b): a retrograde signal from the internal SR (that is, the Ca 2+ depletion of the internal SR) triggers the activation of Orai1 in the sarcolemmal (and t-tubule) membrane. 22, 55

RyR1 along with canonical-type transient receptor potential cation channels (TRPCs) was once believed to be one of the components mediating SOCE. 56, 57, 58 However, skeletal muscle fibers from RyR1-deficient mice still retain SOCE. 12, 59, 60 As might have been expected, both Orai1 and STIM1 are also the proteins that are mainly responsible for SOCE in skeletal muscle. 33, 61, 62 A deficiency of either of these proteins results in the absence of SOCE and induces the development of skeletal myopathy in mice. 12, 63 It is now clear that RyR1 is not a main component of SOCE in skeletal muscle, and the debate continues as to the regulatory role of RyR1 as a component of SOCE. 60, 64

There are several unique characteristics of SOCE in skeletal muscle, which can be compared to SOCE in other cells. First, Orai1 and STIM1 in skeletal muscle show a pre-puncta formation even during resting periods (that is, without the Ca 2+ depletion of the SR). 8, 12, 49 The key factor in understanding the pre-puncta formation in skeletal muscle is the striated muscle-specific triad junction (as mentioned in the Introduction). Closely juxtaposed t-tubule and SR membranes allow skeletal muscle to skip the rearrangement of the SR membrane near the plasma (and t-tubule) membrane during SOCE. The pre-puncta formation by Orai1 and STIM1 occurs either during the myogenesis of skeletal muscle fibers (that is, development) or during the differentiation processes of skeletal myoblasts to mature myotubes (that is, terminal differentiation; myoblasts are the proliferative culture form of satellite cells that are skeletal muscle stem cells). 8, 12, 49 However, it is worth noting that pre-puncta are not the same as functional puncta, because not all puncta mediate SOCE. 8, 49 Further conformational changes of Orai1 and/or STIM1 in pre-puncta seem to be required to evoke SOCE. 65 Therefore, it is helpful to understand that pre-puncta exist in an almost-ready-to-go state. Second, SOCE in skeletal muscle shows much faster kinetics. SOCE in skeletal muscle occurs within 1 s after the Ca 2+ depletion of the SR, which is significantly faster than that in other cells (approximately several seconds to minutes). 12, 62, 66 Pre-puncta formation by Orai1 and STIM1 in the triad junction supports an immediate and rapid delivery of extracellular Ca 2+ to the cytosol during SOCE in skeletal muscle. Although SOCE in skeletal muscle is much faster than it is in other cells, it is still much slower than either the rate of cytosolic Ca 2+ elevation during skeletal muscle contraction or the rate of SR refill with Ca 2+ during skeletal muscle relaxation. Third, STIM1L, an alternatively spliced variant of STIM1 (a longer version of STIM1), is abundantly expressed in skeletal muscle cells, but much less so in other cells. 30, 33 STIM1L interacts with actin as well as with Orai1 and forms permanent clusters, which allows the immediate activation of SOCE—enough to generate repetitive signals within seconds. Therefore, it seems that STIML partly contributes to the rapid activation of SOCE in skeletal muscle. Taken together, skeletal muscle has spatial, temporal and additional resources to operate SOCE.

On the other hand, the SR in skeletal muscle is subdivided by its location, the junctional SR (also called terminal cisternae) and the longitudinal SR (which is not juxtaposed with t-tubule). 4 STIM1 in skeletal muscle is found in the longitudinal SR as well as in the junctional SR. 12 This has suggested a possibility that in addition to STIM1 in the junctional SR for a rapid activation of SOCE without the relocation of STIM1, there could be the other class of STIM1 in skeletal muscle in terms of working mechanism—STIM1 in the longitudinal SR during SOCE relocates to the junctional SR near the t-tubule (this is the same as what STIM1 in other cells does). The existence of the graded SOCE (also called delayed SOCE) in skeletal muscle has been reported, 30, 64, 67 and STIM1 in the longitudinal SR could be responsible for the graded activation of SOCE in skeletal muscle.

There has been no doubt about the existence and significance of SOCE in the physiological phenomena of skeletal muscle. Thus far, however, the ‘degree’ or ‘timing’ of SOCE contribution to skeletal muscle function has remained unclear, and so diverse and intensive research in these areas is required for more integrative information on skeletal muscle physiology in addition to classic knowledge.

Certain in vitro experimental conditions had shown extracellular Ca 2+ entry in skeletal muscle to be surplus Ca 2+ , because skeletal muscle contraction occurs even in the absence of extracellular Ca 2+ . 1, 2, 3, 4 It is worth noting here that the initiation of skeletal muscle contraction (that is, a twitch) is a different concept from the maintenance of contraction. In addition, the duration (that is, maintenance) as well as the peak amplitude of the change in cytosolic Ca 2+ level during a single twitch is considered a significant parameter of the strength of that twitch. According to this trend, the science of extracellular Ca 2+ entry in skeletal muscle has been revisited, and SOCE has been considered the main and well-understood extracellular Ca 2+ entryway in the maintenance of skeletal muscle contraction.

In addition to the roles of SOCE in skeletal muscle contraction, changes in the extracellular Ca 2+ entry via SOCE in skeletal muscle serve as signals to regulate long-term skeletal muscle functions such as muscle development, growth and cellular remodeling, via the activation of various Ca 2+ -dependent pathways and via the changes of intracellular Ca 2+ levels. 68, 69 Orai1 or STIM1 deficiency and a lack of SOCE in patients are symptomatic of the congenital myopathy of skeletal muscle that causes muscular weakness and hypotonia. 70, 71 Patients with a deficiency of Orai1 show impaired SOCE. 70 Orai1 deficiency in mice results in a perinatally lethal condition and is characterized by a smaller body mass. 63 Patients with a deficiency in STIM1 also show muscular hypotonia due to the abrogation of SOCE. 71 A STIM1 deficiency in mice is also perinatally lethal, and is characterized by a failure to show SOCE. 12 Moreover, these mice show a significant reduction in body weight due to skeletal muscle hypotonia and a significant increase in susceptibility to fatigue, but twitch contractions are normal. STIM1 transgenic mice show a significant increase in SOCE in skeletal muscle, as observed in dystrophic skeletal myofibers. 72 These reports suggest that Orai1- and STIM1-mediated SOCE have important roles in the development of skeletal muscle.

Studies on the cellular levels of SOCE in skeletal muscle have progressed. Changes in the expression levels of STIM1 or Orai1 are observed during the terminal differentiation of skeletal myoblasts to myotubes. 12, 49, 69 During the terminal differentiation of mouse skeletal myoblasts to myotubes, substantial Orai1 expression appears beginning on differentiation day 2 (D2). After an additional increase on D3, Orai1 expression is maintained during further differentiation days after a small decrease. 49 On the other hand, STIM1 expression is detected even in myoblasts (that is, before differentiating). 12, 49 STIM1 expression during the terminal differentiation gradually increases until D2 and is maintained during further differentiation days after a small decrease. 12, 49 These marked changes in the expression levels of Orai1 or STIM1 accompany the enhancement of SOCE, which is correlated with observations wherein the enhancement of SOCE has also been observed during the terminal differentiation of mouse or human myoblasts to myotubes. 12, 49, 73 Knockdown of STIM1 reduces SOCE in mouse skeletal myotubes. 59 Likewise, the knockdown of STIM1, Orai1 or Orai3 reduces SOCE in human skeletal myotubes. 73 In addition, the terminal differentiation of human skeletal myoblasts to myotubes is hampered by the silencing of STIM1, Orai1 or Orai3. 73 To the contrary, the overexpression of STIM1 in mouse skeletal myoblasts or C2C12 myotubes (mature forms differentiated from the C2C12 myoblast that is a skeletal muscle cell line) enhances the terminal differentiation. 74 Therefore, SOCE is critical for the remodeling of skeletal muscle after birth (that is, the terminal differentiation) as well as for neonatal muscle growth (that is, development). 75

SOCE also participates in skeletal muscle diseases such as skeletal muscle dystrophy, as well as in physiological phenomena such as the development and terminal differentiation of skeletal muscle. These SOCE-related skeletal muscle diseases are briefly described in the latter part of this review.

TRPCs have also been proposed as mediators of extracellular Ca 2+ entry in skeletal muscle. 33, 76, 77 Skeletal muscle expresses mainly four types of TRPCs: TRPC1; TRPC3; TRPC4; and TRPC6 (TRPC2 appears in extremely lower expression than the others). 78 Little is known about TRPC6 function in skeletal muscle.

TRPC1 functions as a SOCE channel in C2C12 myotubes. 79 SOCE through TRPC1 in C2C12 myoblasts participates in the migration of C2C12 myoblasts and in the terminal differentiation to myotubes via calpain activation. However, there is also a contradictory report that skeletal muscle fibers from TRPC1-deficient mice do not show a difference in SOCE. 76 It is well known that TRPCs form heteromeric channels, with the appearance of homomers among them. 80 The expression of heteromeric TRPC1/4 in mouse skeletal myotubes enhances SOCE. 81 The knockdown of either TRPC1 or TRPC4 in human skeletal myotubes reduces SOCE and significantly delays its onset. 82 The overexpression of TRPC1 or TPRC4 enhances SOCE and accelerates the terminal differentiation of human myoblasts to myotubes. 83 Changes in the SOCE in mouse skeletal myotubes involve changes in TPRC4 expression, 84, 85 but no mechanism has been suggested for these changes. Considering the relatively high expression of TRPC4 in skeletal muscle, more research is needed to reveal the role of TRPC4 in skeletal muscle.

TRPC3 is highly expressed in skeletal muscle, and physiological evidence has implicated the involvement of TRPC3 in many processes of skeletal muscle. 58, 86, 87 The walking of TRPC3-deficient mice is impaired due to abnormal skeletal muscle coordination. 88 TRPC3 heteromerizes with other TRPC subtypes to form functional channels. 78, 80, 89 The heteromerization of TRPC3 with TRPC1 is found in mouse skeletal myotubes and C2C12 myotubes, 90, 91, 92 and it regulates the resting cytosolic Ca 2+ level of the skeletal myotubes. 92 Interestingly, TRPC3 binds to various EC coupling-mediating proteins in mouse skeletal muscle, such as RyR1, TRPC1, JP2, homer1b, MG29, calreticulin and calmodulin. 56, 90, 93 Knockdown of TRPC3 in mouse skeletal myoblasts hampers the proliferation of myoblasts. 94 The expression of TRPC3 is sharply upregulated during the early stages of the terminal differentiation of mouse skeletal myoblasts to myotubes, and it remains elevated in the myotubes compared with that of the myoblasts. 77, 90, 93 Therefore, extracellular Ca 2+ entry through TRPC3 could have important roles in the proliferation and terminal differentiation of skeletal muscle. 77, 93, 94 Skeletal muscle fibers from TRPC3 transgenic mice show an increase in SOCE that results in a phenotype of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) that is caused by a deficiency in functional dystrophin and leads to the progressive weakness of skeletal muscle. 95 TRPC3 has been proposed as a SOCE channel in chick embryo skeletal muscle. 96 On the other hand, TRPC3 in mouse skeletal myotubes is only required to sustain high Ca 2+ levels in the cytosol during EC coupling for the full gain of EC coupling, and the role of TRPC3 is independent of the Ca 2+ amount in the SR. 2, 77 Therefore, the role of TRPC3 as a SOCE channel in skeletal muscle remains unclear, although TRPC3 is definitely related to SOCE in skeletal muscle. Considering that TRPC3 binds to MG29 or JP2 in mouse skeletal myotubes, 90, 97, 98 it is possible that TRPC3 indirectly regulates SOCE via other proteins such as MG29 or JP2 in skeletal muscle (this is further discussed in the latter part of this review).

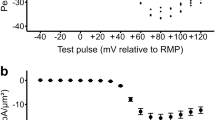

Excitation-coupled Ca 2+ entry (ECCE; Figure 1a) is another extracellular Ca 2+ entry that is basically different from SOCE. 99 Prolonged and repetitive depolarization of mouse skeletal myotubes evokes ECCE. 99 ECCE is absent in both dyspedic and dysgenic mouse skeletal myotubes that lack functional RyR1 and DHPR, respectively. 99, 100 Therefore, functional coupling between DHPR and RyR1 is required to evoke ECCE. The proteins responsible for ECCE remain a matter of debate, although the existence of ECCE is accepted. 99, 101, 102 It is known, however, that neither Orai1 nor TRPC3 is the Ca 2+ channel for ECCE. 59, 77

A significant difference between ECCE and SOCE is that Ca 2+ depletion in the SR is not required for ECCE. 99, 103 The direction of signaling is another big difference. SOCE is a matter of inside-out (retrograde) signaling via the interaction between STIM1 and Orai1 due to Ca 2+ depletion in the SR, whereas ECCE is one example of outside-in signals via coupling between DHPR and RyR1 due to the depolarization of the t-tubule membrane (Figure 1b). 12, 62, 99, 100 Finally, existence of both DHPR and RyR1 is required for ECCE, but not for SOCE. 99, 100 Therefore, ECCE and SOCE are two fundamentally distinct extracellular Ca 2+ entryways across the sarcolemmal (and t-tubule) membrane in skeletal muscle. It is still possible, however, that the two different extracellular Ca 2+ entryways could partially overlap at some point and communicate with one another, because prolonged and repetitive depolarization of skeletal myotubes (which can evoke ECCE) could also induce changes in the Ca 2+ amount of the SR (which can evoke SOCE). 60, 104, 105

In this section, several, but not all, of the proteins that are related to, or that regulate, the extracellular Ca 2+ entry into skeletal muscle are briefly reviewed, particularly those that are currently drawing our attention.

As introduced above, skeletal muscle utilizes a highly specialized cellular architecture for various Ca 2+ movements (Figure 1c), which is referred to as the triad junction. This provides a unique structure for direct interaction between DHPR and RyR1, or STIM1 and Orai1, and, subsequently, for rapid intracellular Ca 2+ release during EC coupling or the rapid onset of SOCE. 1, 2, 3, 4, 33, 61, 62, 66 Among the four subtypes of JPs, JP1 and JP2 are expressed in skeletal muscle. 106 JP1 and JP2 mediate the formation and maintenance of the triad junction in skeletal muscle by physically linking the t-tubule and SR membranes. 7, 107, 108 JP1-deficient mice show an abnormal triad junction and neonate lethality. 7, 109 The knockdown of JP1 and JP2 in mouse skeletal muscle fibers or C2C12 myotubes also leads to a disorganization of the triad junction, and SOCE is remarkably decreased by the ablations of JP1 and JP2. 67

Both JP1 and JP2 are related to TRPC3 in skeletal muscle. 77, 90, 98 Knockdown of TRPC3 in mouse skeletal myotubes increases JP1 expression and decreases intracellular Ca 2+ release from the SR in response to contractile stimuli. 77 To the contrary, the skeletal muscle of JP1-deficient mice shows decreases in the expressions of TRPC3 and SOCE due to the diminished expressions of Orai1 and STIM1. 85 On the other hand, JP2 binds to TRPC3 in mouse skeletal myotubes. 90, 98 JP2 mutation at S165 (found in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 110 ) in mouse skeletal myotubes induces hypertrophy, and the hypertrophied skeletal myotubes show decreases in the ability to bind to TPRC3 and in the intracellular Ca 2+ release from the SR in response to contractile stimuli. 97 Another JP2 mutation at Y141 (found in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 110 ) in mouse skeletal myotubes also leads to hypertrophy along with an abnormal triad junction and an increase in SOCE due to an increased Orai1 expression. 8 Therefore, JP1 and JP2 in skeletal muscle could directly or indirectly regulate cross talk among proteins on the t-tubule and SR membranes during EC coupling or SOCE, as well as the formation and maintenance of triad formation.

MG29, one of the synaptophysin proteins, is exclusively expressed in skeletal muscle (in both t-tubule and SR membranes). 111, 112, 113 Along with the primary roles of JPs, MG29 also contributes to the formation and maintenance of the triad junction in skeletal muscle. 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10 Skeletal muscle from MG29-deficient mice is characterized by partial malformations of the triad junction such as swollen and irregular t-tubules and incomplete SR structures. 10 Functional abnormalities such as low twitch force and severely impaired SOCE are also found in the skeletal muscle fibers of MG29-deficient mice. 10, 60

MG29 is correlated with other skeletal proteins in terms of SOCE. Mice skeletal muscle fibers from a knockdown of sarcalumenin (a Ca 2+ -binding protein in the lumen of SR) show increases in MG29 expression, SOCE and fatigue resistance. 104 Co-expression of MG29 and RyR1 in a heterologous expression system causes apoptosis due to excessive SOCE. 114 MG29 interacts with TRPC3 at its N-terminal portion in mouse skeletal myotubes. 90, 115 The disruption of MG29–TRPC3 interaction decreases intracellular Ca 2+ release from the SR in response to contractile stimuli without affecting RyR1 activity. 115 Interestingly, the knockdown of TRPC3 in mouse skeletal myotubes from α1sDHPR-null muscular dysgenic mice involves significant reductions in Orai1, TRPC4 and MG29 expression. 94 It seems that MG29 in skeletal muscle indirectly regulates both intracellular Ca 2+ release and SOCE by way of other skeletal proteins.

MG53 (also called TRIM72) is a muscle-specific tripartite motif (TRIM) family protein, and skeletal muscle is the major tissue that expresses it. 116, 117 MG53 in skeletal muscle participates in membrane repair along with dysferlin, polymerase I and transcript release factor, and non-muscle myosin type IIA. 116, 117, 118 MG53 interacts with phosphatidylserine to associate with intracellular vesicles. During the membrane repair process by MG53, injury to a plasma membrane induces oxidation-dependent vesicular oligomerizations via the formation of disulfide bonds among MG53 proteins on the vesicles. The oligomerized vesicles fuse to the injured plasma membrane and reseal it. Membrane repair by MG53 is not restricted to skeletal muscle because MG53 is detected in the circulating blood of normal mice. 119 Indeed, the intravenous delivery or inhalation of recombinant MG53 reduces symptoms in rodent models of acute lung injury and emphysema. 120

MG53 also has other important roles in intact skeletal muscle, which are correlated with its membrane repair ability. MG53 facilitates the terminal differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts by enhancing vesicle trafficking and membrane fusion. 117, 121 MG53-deficient mice show progressive myopathy and a reduced exercise capability that is associated with a defective capacity for membrane repair. 116 SOCE is greatly enhanced in the skeletal muscle fibers of mdx mice, which is a mouse model of human DMD. 122 Interestingly, the subcutaneous injection of purified MG53 to mdx mice alleviates skeletal muscle pathology by promoting membrane repair. 119 Muscle-specific overexpression of MG53 in a δ-sarcoglycan-deficient hamster model of muscular dystrophy ameliorated the pathology by enhancing membrane repair. 123 Recent reports showed that MG53 binds to Orai1 and colocalizes with Orai1 in the sarcolemmal membrane of mouse skeletal myotubes, and established that MG53–Orai1 interaction enhances SOCE along with increases in the expression levels of TRPC3, TRPC4 and calmodulin 1. 84

MG53 binds to TRPC3, 84 but the functional relationship remains unknown. On the other hand, MG53 attenuates SERCA1a activity by binding to SERCA1a at a high cytosolic Ca 2+ level (like that seen during skeletal muscle contraction) in mouse skeletal myotubes. 121 Considering that SERCA1a activity is directly related to the Ca 2+ amount of the SR 2, 6 and that Orai1 is the major Ca 2+ entry channel during SOCE in skeletal muscle, MG53 is a great helper of Orai1 activation during SOCE in skeletal muscle.

STIM1 binds to SERCA1a and maintains the full activity of SERCA1a at a high cytosolic Ca 2+ level (like that during skeletal muscle relaxation just after contraction) in mouse skeletal myotubes. 124 The regulation of SERCA1a activity by STIM1 is opposite to that by MG53. 121 This suggests that STIM1 and MG53 could regulate intracellular Ca 2+ distribution between the SR and the cytosol via the regulation of SERCA1a activity. STIM1 attenuates DHPR activity by binding to DHPR in mouse skeletal myotubes, and subsequently downregulates intracellular Ca 2+ release in response to contractile stimuli. 49 Therefore STIM1 functions as an all-around player in the diverse Ca 2+ movements of skeletal muscle: in skeletal muscle, STIM1 is a faithful guardian of SR Ca 2+ storage because STIM1 serves as a monitoring sensor of Ca 2+ depletion in the SR during SOCE, as a promoter of the refilling of Ca 2+ into the SR during skeletal muscle relaxation and as an attenuator of DHPR activity during skeletal muscle contraction.

It is a great puzzle what protein(s) or signaling molecule(s) could function as a button(s) to switch the role of STIM1 in the diverse Ca 2+ movements or to balance the STIM1 functions in diverse Ca 2+ movements of skeletal muscle. It seems that the characteristics of STIM1 as an all-around player are also linked to the wonder of skeletal muscle―how long-term events in skeletal muscle such as fatigue and the aging progress are regulated (briefly described in the latter part of this review).

CSQ is a major Ca 2+ -buffering protein that has a high capacity for, and a moderate-affinity to, Ca 2+ , and is present in the lumen of the SR in skeletal myoblasts and myotubes. 1, 5, 125 CSQ1-deficient mice show an altered ultrastructure such as a more extensive triad junction and a decrease in the volume of junctional SR. 126 At high temperature (41 °C), CSQ1-deficient mice show hyper-contractility with high mortality, 127 although they show even less intracellular Ca 2+ release in response to contractile stimuli. 126 The hyper-contractility with high mortality is a symptom also seen in patients with malignant hyperthermia (MH) 128 or in mouse models of MH 129, 130 (MH was briefly described in the latter part of this review).

Knockdown of CSQ1 in mouse skeletal muscle fibers displays a significant increase in SOCE and a subsequent elevation in cytosolic Ca 2+ levels. 131 Overexpression of CSQ1 in C2C12 myotubes enhances the intracellular Ca 2+ release in response to contractile stimuli by increasing the Ca 2+ amount in the SR, but SOCE is inhibited by the overexpression of CSQ1. 132 The inhibition of SOCE by CSQ1 is due to the binding of CSQ1 to STIM1, which interferes with STIM1 dimerization and the binding between STIM1 and Orai1. 133, 134 Therefore, CSQ1 and STIM1 have a relationship of action and reaction in terms of evoking SOCE, and the inhibition of SOCE by CSQ1 is one of inside-out signals (Figure 1b).

Regeneration is a unique attribute of skeletal muscle. 135 Satellite cells in skeletal muscle are the unchangeable players of skeletal muscle regeneration. 136 Endothelial cells also are important players in skeletal muscle regeneration by promoting angiogenesis at the sites of skeletal muscle regeneration. Angiopoietin 1 (Ang1), one of the angiogenic factors, has important roles in vascular endothelial cells for vascular integrity and maturation during angiogenesis. 137, 138, 139 Activation of Tie2 receptor by the binding of Ang1 is critical for endothelial cell survival and the prevention of vascular leakage. 139, 140, 141, 142, 143

Ang1 and Tie2 receptors are expressed in human and mouse satellite cells and promote their self-renewal. 144 Ang1 adheres to C2C12 myoblasts by binding to α6 and β3 integrins and enhances cell survival. 145 Ang1 also exhibits myogenic potential by promoting the proliferation, migration and the terminal differentiation of mouse skeletal myoblasts to myotubes by binding to α7 and β1 integrins. 146 Recombinant Ang1 increases survival, proliferation, migration and the terminal differentiation of human skeletal myoblasts to myotubes. 147 Ang1 potentiates the intracellular Ca 2+ release of mouse skeletal myotubes in response to contractile stimuli along with the increased expression of Orai1. 146 Ang1 and Ang2 exert similar effects on human and mouse skeletal myoblasts and myotubes. 148 Considering that numerous events during the development of skeletal muscle are Ca 2+ -dependent, 149 a deeper understanding of the positive roles of Angs in the Ca 2+ movements of skeletal muscle could help reveal the secret of skeletal muscle regeneration.

Skeletal muscle aging, fatigue and diseases are extremely complex issues in terms of their causes, onset, progress, symptoms and prognosis. In this section, the involvement of SOCE in skeletal muscle aging, fatigue and diseases is briefly reviewed.

Skeletal muscle fibers from aged mice (26–27 months, which correspond to ~70 years for humans) show a severe reduction in SOCE. 150 Defective SOCE contributes to reduced contractile force in aged mouse skeletal muscle, particularly during high-frequency stimulation. 151 However, the reduction in SOCE is not the result of altered expression levels of either STIM1 or Orai1. 150 In accordance with this, the expression levels of neither STIM1 nor Orai1 change during skeletal muscle aging in humans, mice or flies. 152 Interestingly, reductions in SOCE and contractile force also appear in the fibers of MG29-deficient young mice. 150 MG29 expression is significantly decreased in aged skeletal muscle. 153 Therefore, changes in both SOCE and MG29 expression are related to skeletal muscle aging. If MG29 is either directly or indirectly related to TRPC3 and TRPC4, 90, 115 there is a possibility that extracellular Ca 2+ entry via TRPC3 and/or TRPC4 could participate in the aging of skeletal muscle. For both a broader and deeper understanding of skeletal muscle aging, please refer to a publication by Zahn et al., 152 where the transcriptional profiling of aging in human, mouse and fly muscle is well defined using common aging signature sets.

The mass and/or strength of skeletal muscle is deteriorated in some individuals, 150 which is called sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is the result of a wasting of skeletal muscle protein, a loss of functionality and an increase in susceptibility to fatigue. 154, 155 Sarcopenia also occurs with age even in normal individuals, to some degree, and so it is considered a normal part of healthy aging. Repeated or intensive use of skeletal muscle leads to skeletal muscle fatigue, and many factors are involved in the fatigue process. 104, 105 Increases in susceptibility to fatigue are shown in animal models with chronic degenerative skeletal muscle diseases such as atrophy and age-related sarcopenia. 154, 155 Skeletal muscle fibers from transgenic mice with dominant-negative Orai1 display a lack of SOCE and an increased susceptibility to fatigue. 65 Therefore, defects in slow and cumulative Ca 2+ entry through SOCE (fast enough but relatively slower than the intracellular Ca 2+ release from the SR during EC coupling) could be one of the fatigue-inducing factors. Transgenic mice with sarcolipin, a regulator of SERCA1a in skeletal muscle, are more resistant to fatigue, and skeletal muscle fibers from these mice show an increase in SOCE. 156 The skeletal muscle fibers of CSQ1-deficient mice show an increased susceptibility to fatigue in response to prolonged or repetitive stimuli. 157 Skeletal muscle fibers from sarcalumenin-deficient mice show increases in MG29 expression, SOCE and fatigue resistance. 104 MG29-deficient mice show increased susceptibility to fatigue due to an abnormal triad and a severe dysfunction in SOCE. 60, 158, 159 Therefore, MG29 is related to fatigue as well as to aging in skeletal muscle. It is possible that TRPC3 could also be involved in skeletal muscle fatigue because MG29 interacts with TRPC3 and regulates intracellular Ca 2+ release from the SR in response to contractile stimuli in mouse skeletal myotubes. 77, 90, 115 On the other hand, TRPC1-deficient mice present an important decrease in endurance during physical activity, and skeletal muscle fibers from TRPC1-deficient mice show a decrease in intracellular Ca 2+ release from the SR in response to repetitive stimuli. 76 However, the decrease is not dependent on SOCE, and extracellular Ca 2+ entry via TPRC1 is involved.

Aberrant Ca 2+ movements in skeletal muscle cause various skeletal muscle diseases. Interest in the involvement of SOCE in the pathophysiology of skeletal muscle diseases is an emerging area of research. A loss-of-function mutant of Orai1, R91W, is found in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency, and these patients also show a significant level of skeletal muscle myopathy. 18, 40 Patients with a loss-of-function mutation of STIM1, E136X, also show severe combined immunodeficiency and congenital myopathies such as nonprogressive muscular hypotonia due to a lack of SOCE. 71 Patients with another STIM1 mutation, R429C, also show muscular hypotonia. 160 Changes in long-term contractility that are characteristics of STIM1- or Orai1-deficient patients or mice 41 could provide clues to the understanding of long-term events such as the progression of fatigue and the aging of skeletal muscle.

Tubular aggregates are unusual membranous structures within muscle fibers that result in tubular-aggregate myopathy (TAM), and are among the secondary features that are representative indicators of numerous human myopathies. 161 Gain-of-function mutations in Orai1 (G98S, V107M or T184M) are found in patients with TAM, and the Orai1 mutants in a heterologous expression system are responsible for increases in SOCE. 162 Patients with one of four STIM1 missense mutations in EF hand (H72Q, D84G, H109N or H109R that are constitutively active forms of STIM1) show atrophy, TAM, progressive muscle weakness with excessive SOCE and significantly higher cytosolic Ca 2+ levels. 163

DMD, a lethal disease, is a form of muscular dystrophy that is characterized by progressive muscle wasting. 95 Abnormally elevated SOCE is one of the causes of DMD pathogenesis. The upregulation of SOCE in skeletal muscle fibers from mdx mice is accompanied by significant increases in STIM1 and Orai1 expression. 122, 164, 165 Surprisingly, undifferentiated myoblasts from mdx mice also show enhanced SOCE, particularly an increased rate of SOCE with a significantly elevated level of STIM1 expression. 166 The transgene expression of a dominant-negative Orai1 mutant in a mdx or a δ-sarcoglycan-deficient mouse model of muscular dystrophy significantly reduces the severity of muscular dystrophies. 72 Skeletal muscle fibers from muscle-specific STIM1 transgenic mice show characteristics of DMD, including a significant increase in SOCE. 72 TRPC3 transgenic mice show a phenotype of DMD, which suggests that an increase in SOCE through TRPC3 is another cause for the pathology of DMD. 167

MH is a pharmacogenic disorder of skeletal muscle. 130 Volatile anesthetics given to patients with MH can lead to life-threatening skeletal muscle contracture and an increase in body temperature due to the uncontrolled elevation of cytosolic Ca 2+ levels via the uncontrolled activation of RyR1, and finally to sudden death. The skeletal muscle fibers of patients with MH show the occurrence of SOCE even within the clinical range of volatile anesthetics. 168 CSQ1 deficiency in mice induces a hyper-contractile state at elevated ambient temperature with a high degree of mortality, 127 similar to the symptoms of MH patients. 128 These MH-like symptoms are also observed in the knockout of either CSQ1/2 or RyR1 knock-in mice. 129, 131, 169 The elevation in the body temperature of the mice is related to the increase of SOCE in the skeletal myotubes. 131, 169 Central core disease (CCD) involving progressive muscle weakness is another well-known skeletal muscle disease, and patients with CCD are also at high risk for the development of MH. 170 Therefore, the involvement of SOCE in the progression of CCD could lead to an understanding of the pathology of CCD.

TRPC3 171, 172 and MG53 116, 119, 123, 173 are also related to skeletal muscle diseases involving extracellular Ca 2+ entry, and other possible factors causing skeletal muscle diseases have been reviewed or reported in several publications. 58, 64, 174, 175

This review focuses on extracellular Ca 2+ entry, particularly SOCE, which participates in the various physiological and pathophysiological phenomena of skeletal muscle such as contraction and relaxation, development, terminal differentiation, aging, fatigue and disease. It is surprising that SOCE even contributes to mitochondrial Ca 2+ movements in skeletal muscle. 72, 176 In short, it seems that the role of extracellular Ca 2+ entry such as SOCE fine tunes every function of skeletal muscle.

Exercise-mediated hypertrophy in skeletal muscle leads to increases in both muscle mass and cross-sectional areas. 177 Unlike cardiac muscle, hypertrophy (and hyperplasia) in skeletal muscle is related to healthy phenomena such as muscle growth, repair and regeneration. 178, 179 Healthy hypertrophy in skeletal muscle involves increases in SOCE. 75, 97 Considering that SOCE is involved in both the health and disease of skeletal muscle, extracellular Ca 2+ entry, including SOCE in skeletal muscle is a double-edged sword with respect to physiological and pathophysiological functions.

The roles of SOCE in cardiac muscle are less clear and more complex than those in skeletal muscle. The advances in skeletal muscle studies on forms of extracellular Ca 2+ entries, including SOCE could help provide a better understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of the heart.

This work was supported by the Mid-career Researcher Program through National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. NRF-2014R1A2A1A11050963 and NRF-2017R1A2B4005924 (to EHL) and 2014R1A2A1A11050981 (to C-HC)).

Author contributions

C-HC, JSW, CFP and EHL contributed to the literature search. C-HC and EHL wrote the manuscript. CFP, JSW and EHL discussed all the contents of the manuscript.